Harvest Weed Seed Control

Weed seedbanks are the primary source of annual weed infestations. Reducing seedbank replenishment is, therefore, critical for effective weed management. Frequently, weeds survive herbicide applications or other control tactics and set seed. These escaped weeds can often be seen poking out above the canopy. Weed seeds can still be managed before they replenish the soil weed seed bank with the harvest weed seed control (HWSC) tactics discussed below. The success of HWSC practices depends on the biological attribute of seed retention at crop maturity: HWSC is only effective for weed species that do not shatter (meaning drop their seeds) prior to mechanical harvest.

The Soil Seedbank

“Soil seedbank” refers to weed seeds present in the soil. The soil seedbank serves as the source of next season’s weed problems. The majority of seeds in the soil were deposited by plants that escaped control in previous years. Due to seed dormancy, weed seeds can remain viable in the soil for many years and often emerge over several weeks during the growing season. Seed dormancy, prolonged viability, and extended emergence periods make it easier for weeds to survive across a wide range of environments and management tactics. Current management recommendations target weed seed production to prevent additions to the soil seedbank. Recommendations include controlling weeds while they are small and susceptible to weed control tactics, removing weeds that escape control, and managing weeds that produce viable seeds to minimize their impact on the soil seedbank. These late-season practices are not new, but due to wide-spread herbicide-resistance they are being revisited with new technology. In this video Dr. Mandy Bish explains the importance of understanding the weed seedbank and why preventing weeds from producing seeds is so important.

Soil Seedbank Management

Currently there are no economical methods to kill weed seeds once they enter the soil. Weed management practices focus on controlling weeds early in the growing season with herbicides and cultivation, then following up to manage those weeds that escape control and prevent seeds from entering the soil. Studies have demonstrated that preventing seeds from returning to the soil can rapidly reduce the seedbank and resulting weed densities. Allowing weeds to produce viable seeds, however, can cause rapid increases in weed densities. Stopping seeds from entering the seedbank can be achieved by:

- Preventing weeds from producing seeds (no seeds, no weeds)

- Enhancing weed seed predation

- Increasing seed mortality

- Removing seeds from the field before the seeds are shed

- Using any HWSC method that fits your cropping system to either concentrate or destroy weed seeds (e.g., chaff lining, impact mills, etc.) if weeds do produce viable seeds.

There has been a renewed emphasis on increasing seed mortality, mechanically removing seeds from the field, and altering the placement of seeds. These tactics were used before the wide-spread availability of herbicides. Because of technological advances in machinery, these tactics are again being researched and adapted for use in the US and around the world.

How to Prevent Additions to the Soil Weed Seed Bank

As cash crop harvest approaches you may discover that weeds have escaped your control efforts and are setting seeds. These weeds may be very visible, poking their heads above the canopy of the cash crop. Weeds below the crop canopy can also set seed. When you go to harvest the cash crop, you are at risk of spreading the weed seeds through your fields. These escaped weeds will create an even bigger problem next year if they are allowed to add the seeds they have produced back to the soil weed seedbank, or to spread their seeds to new fields by hitching a ride on harvest equipment. You still have a chance to prevent this from happening.

- Scout your fields prior to harvest.

- You can scout using drones or other means such as physically walking the fields.

- Know where the problem areas are: map them out.

- Plan to harvest weed-free areas first and weedy areas last.

Limit the spread of weed seeds through the field and from weedy fields to clean ones. Clean the combine before leaving a field. A single Palmer amaranth plant can produce hundreds of thousands of seeds – planning your harvest strategy and cleaning equipment diligently is well worth the time. Remember: scout, map, and plan prior to harvesting to Get Rid of Weeds!

Soil Seedbank Management Timing

Prior to planting

The most common tactics to reduce the soil seedbank include crop rotation and tillage. Diverse crop rotations allow for a diversification of other supporting IWM tools, such as herbicides, tillage, and crop competition. Diversified crop rotations are rarely used to manage the soil weed seedbank. The use of only one (or a few) cash crops ultimately allows weeds with similar traits to thrive, replenishing the weed seedbank annually. Tillage can both increase the soil seedbank (by burying seeds) and decrease it (by unearthing buried seeds that may germinate early and die). The effect of deep tillage on the soil seedbank can be gauged by knowing the main weed species in a field and understanding how long the seeds of the species stay viable: deep tillage is a better choice for short-lived seeds. Grass weeds tend to have less persistent seeds than broadleaf weeds. Strategic deep tillage affects seedbanks depending on weed traits such as germination and seed size. A specific tillage tactic to manage the seedbank is the stale seedbed method. Stale seedbed management uses tillage to promote weed germination so that another management tactic can then be used to kill weed seedlings prior to crop planting, reducing the size of the soil seedbank. Crop rotations and tillage are fundamental for weed management, but management decisions tend to prioritize economic and logistic factors over effects on weeds.

Prior to harvest

Hand-pulling:

Sometimes weeds escape chemical controls and set seed, making hand-pulling the only option in many cases if HWSC has not been planned ahead of time. Weeds such as Palmer amaranth and waterhemp set viable seeds in a short period of time and so should be completely removed from the field in order to prevent them from adding the soil seedbank.

During Harvest

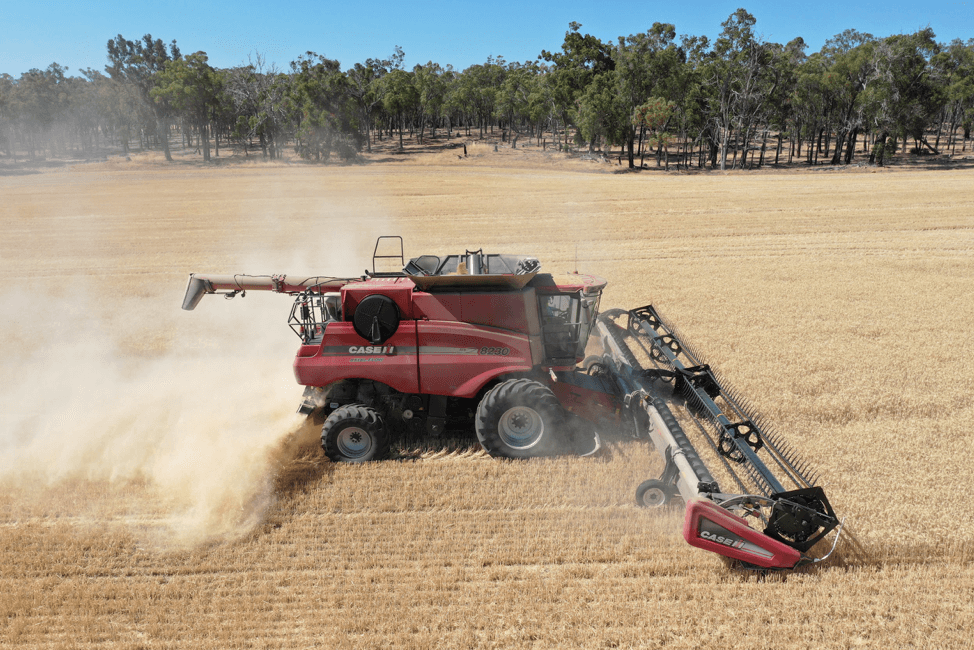

Harvest Weed Seed Control:

Harvest weed seed control (HWSC) is an approach to managing the soil seedbank that focuses on cultural and mechanical options to reduce the impact of seeds from escaped weeds at harvest time. All HWSC methods/technologies are based on separating weed seeds from the chaff fraction when harvesting the cash crop. The final destiny of the weed seeds will depend on the HWSC method used. Some of them concentrate weed seeds in rows, lines, bales, or dumps, while others destroy weed seeds with a mill before they can drop to the ground.

HWSC tactics include:

- Narrow windrow burning

- Chaff lining

- Chaff tramlines

- Impact mills

- Chaff carts

- Bale direct system

Narrow windrow burning is relatively easy to adopt and can provide good results. Both small and large size weed seeds are controlled. This tactic involves a chute that is attached to the rear of the combine that concentrates the chaff and straw residues into a narrow windrow, which is later burned. Costing around $250 in materials to modify a combine it is also an inexpensive tactic. However, this method is time consuming, removes most of the field ground cover, has a risk of fire escape, may not be legal in all jurisdictions, is not an option for all crops (e.g., corn), and it is difficult to achieve a good burn in long windrows. Narrow windrow burning requires some trial and error. Harvesting low is key to obtaining more crop residue to burn. Choosing the right time and conditions to burn is critical. A light wind is ideal, but be careful of a gusty day. Current research suggests that narrow windrow burning works best in wheat and soybean cropping systems, but other systems are being tested.

Chaff lining is also a cost effective HWSC method. Chaff lining uses a chute to divert only the chaff fraction into a narrow row in the center of the harvester, while the rest of the crop residue is spreadly evenly behind the combine. While weed seeds are returned to the soil, they are in narrow lines instead of being spread across the entire field. The chaff material is allowed to rot and decay. These lines can also be managed with focused weed control tactics, such as herbicide applications, at a site specific level.

Chaff tramlining orms the chaff material into narrow rows on dedicated wheel tracks during harvest and relies on a mulch effect to prevent weed seed germination and emergence, as in chaff lining (above). Chaff tramlining equipment runs around $15,000 to $18,000 depending on your harvester brand and model.

Impact mills, such as the integrated Harrington Seed Destructor, the Seed Terminator, the Canadian Redekop system, and the WeedHOG are integrated into the back of the combine where an impact mill physically destroys weed seeds in the chaff fraction. The amount of weed seeds contained in the chaff fraction will depend on the weed species present and on how many of the seeds are retained on the weed before harvest. Impact mills can be highly effective, with over 95% destruction of the weed seeds that enter the mill. Current impact mills are expensive and not available in most countries.

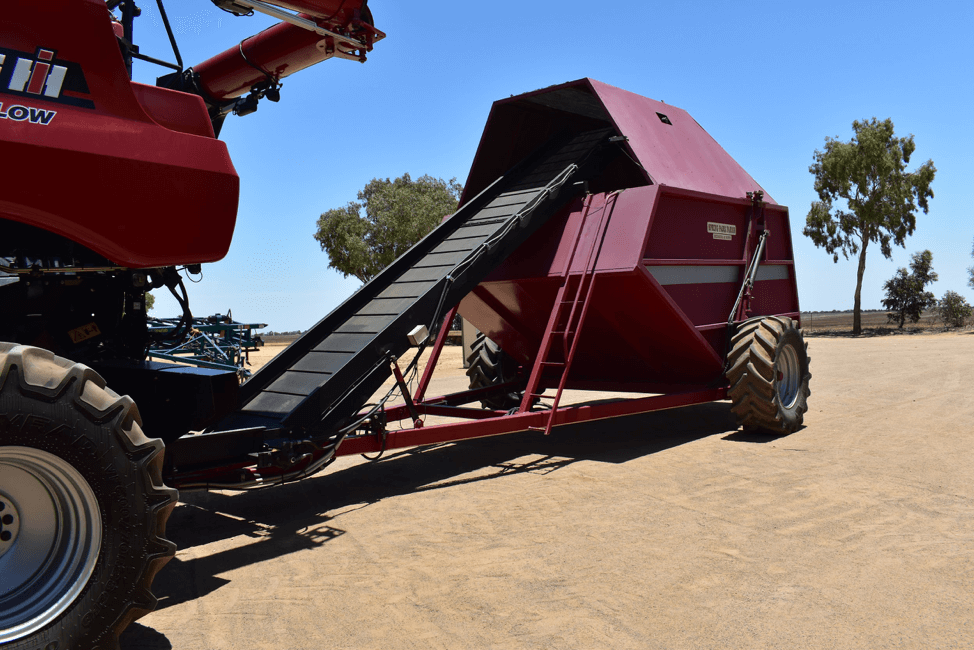

Chaff carts are the simplest HWSC system, consisting of a chaff collection and transfer mechanism that is attached to a combine that delivers the chaff fraction to a bulk collection bin, usually a trailing cart, that can be physically removed from the field so the chaff can be burned or grazed. Major downsides to this method are that it adds extra length to the combine so it can be difficult to navigate in small fields and narrow alleys and it requires extra time to empty the carts.

All HWSC methods are similarly effective, but come with different initial costs, operating costs, and residual costs. Additional pros and cons related to feasibility and level of nutrient removal or redistribution should also be considered when deciding what works best for your system. The best HWSC method for your farm depends on cost and other management concerns.

Table 1: Pros and cons of the six different HWSC methods.

| Total Cost | Objective | Soil Nutrient Removal | Pros | Cons | |

| Chaff lining | low | Concentrate weed seeds in a thin row for future management | low | Easy to use and low cost. Low residue removal. | Limited research on managing weeds in the chaff lines. |

| Chaff tramlining | low/medium | Concentrate weed seeds in a thin row for future management | low | Chaff goes into tramlines. Low residue removal. | Soil compaction. |

| Windrow burning | low/medium | Build a chaff + straw row for future burning | high | Up to 95% weed seed destruction in certain residues. | Risk of fire escapes, may be restricted. |

| Impact mills | high | Destroy weed seeds during harvest | low | Highly effective on a wide range of weed seed sizes. | High initial start up costs. |

| Bale direct | medium | Concentrate weed seeds in bales | high | Adds value to diversified rotation farms. High value bales. | Small market.

High capital cost |

| Chaff cart | medium | Concentrate weed seeds coming from chaff | low | Easy to use. | Slows harvest operation towing the cart and chaff disposal. High capital cost |

All HWSC methods are similarly effective, but come with different initial costs, operating costs, and residual costs. Additional pros and cons related to feasibility and level of nutrient removal or redistribution should also be considered when deciding what works best for your system. The best HWSC method for your farm depends on cost and other management concerns.

Our Current Research on HWSC

Our research started four years ago with three ongoing large plot field trials in Urbana-Champaign, IL; Beltsville, MD; and Fayetteville, AR. These three locations are examining how the use of different IWM tactics can reduce the soil seedbank and combat herbicide resistant weeds. Tactics under investigation include the use of crop rotations, cover crops, impact mills, and narrow windrow burning.

Several field trials have been conducted testing narrow windrow burning in soybean, grain sorghum, and wheat cropping systems at various locations. More recently, research is being conducted in small plots and on farms to adapt chaff lining (a well-proven technology in Australian wheat) to soybean in the US.

Our efforts are spread all over the country with the hope that region- or state- specific trials will help inform growers of the practices best suited for their farms. As our research progresses, our goals are to help growers improve their use of IWM and to make use of HWSC where needed and feasible to Get Rid of Weeds.

Authors

- Mark VanGessel

- Kara Pittman

- Victoria Ackroyd,

- Michael Flessner

- Lovreet Shergill

- Claudio Rubione

Citations

- Bicksler AJ, Masiunas JB (2009) Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) suppression with buckwheat or sudangrass cover crops and mowing. Weed Technol 23:556–563

- Mirsky SB, Ackroyd VJ, Cordeau S, Curran WS, Hashemi M, Reberg-Horton SC, Ryan MR, Spargo JT (2017) Hairy vetch biomass across the eastern United States: effects of latitude, seeding rate and date, and termination timing. Agron J 109:1510–1519

- Mirsky SB, Curran WS, Mortenseny DM, Ryany MR, Shumway DL (2011) Timing of cover-crop management effects on weed suppression in no-till planted soybean using a roller-crimper. Weed Sci 59:380–389

- Myers R, Weber A, Tellatin S (2019) Cover crop economics: Opportunities to improve your bottom line in row crops. SARE Tech Bull

- PennState Extension (2010) Suppressing weeds usıng cover crops in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania State University

- Ruis SJ, Blanco-Canqui H, Creech CF, Koehler-Cole K, Elmore RW, Francis CA (2019) Cover crop biomass production in temperate agroecozones. Agron J 111:1535–1551

- Snapp SS, Swinton SM, Labarta R, Mutch D, Black JR, Leep R, Nyiraneza J, O’Neil K (2005) Evaluating cover crops for benefits, costs and performance within cropping system niches. Agron J 97:322–332