Herbicide Control

Extensive information exists about herbicide options for herbicide intensive weed control. Many state extension programs publish current recommendations for effective control and are an excellent source of unbiased information. This page is designed to discuss the principles behind herbicide selection and to be complementary to state recommendations.

Mix Together Effective Sites of Action to Decrease Herbicide Resistance Development

Growers have relied on herbicides as the main tool for managing weeds in grain crops, preventing weeds from reducing yields and interfering with crop management and harvest. Reliance on the same or similar herbicides has resulted in weed biotypes evolving resistance to herbicides. Herbicide-resistant weed biotypes are no longer controlled by herbicides that previously killed them. New strategies are necessary to control these resistant biotypes. It is important to prevent herbicide-resistant weed biotypes from developing in the first place.

Reducing the risk of developing herbicide-resistant biotypes requires an integrated approach to weed control (IWM). Integrating prevention, mechanical, cultural, and biological as well as strategic chemical control is necessary to forestall herbicide resistance. When it comes to chemical weed control, farmers are hearing about rotating and diversifying herbicides, but the concept is often not explained.

Managing herbicide resistance requires an understanding of the herbicide site of action. Herbicide containers and labels now display a herbicide group number that identifies the site of action. While using different and multiple herbicide sites of action is important, understanding how to use “effective herbicide site of action” is critical for addressing herbicide resistance.

Read more on herbicide effective site of action and how to implement an effective herbicide program,

1st video: Effective Site of Action and How it Should Be Used.

2nd video: “Should I Rotate Herbicides or Tank Mix Them?”

Research from past few years has shed light on how important it is to tank-mix herbicides compared to rotating herbicides.

In this video, Dr. Patrick Tranel explains his farm-based survey of over 100 Illinois farmers who tank-mixed herbicides compared to using them in sequence. This video explains why tank mixing herbicides is the best option to practice and encourages farmers and professionals to select at least two “Effective Site of Action Herbicides” as a consistent strategy for weed resistance management.

3rd video: A Deep-Dive into Tank Mixing Herbicides Compared to Rotating Them

Dr. Tranel explains why tank mixing is a more effective approach to resistance management than sequential applications.

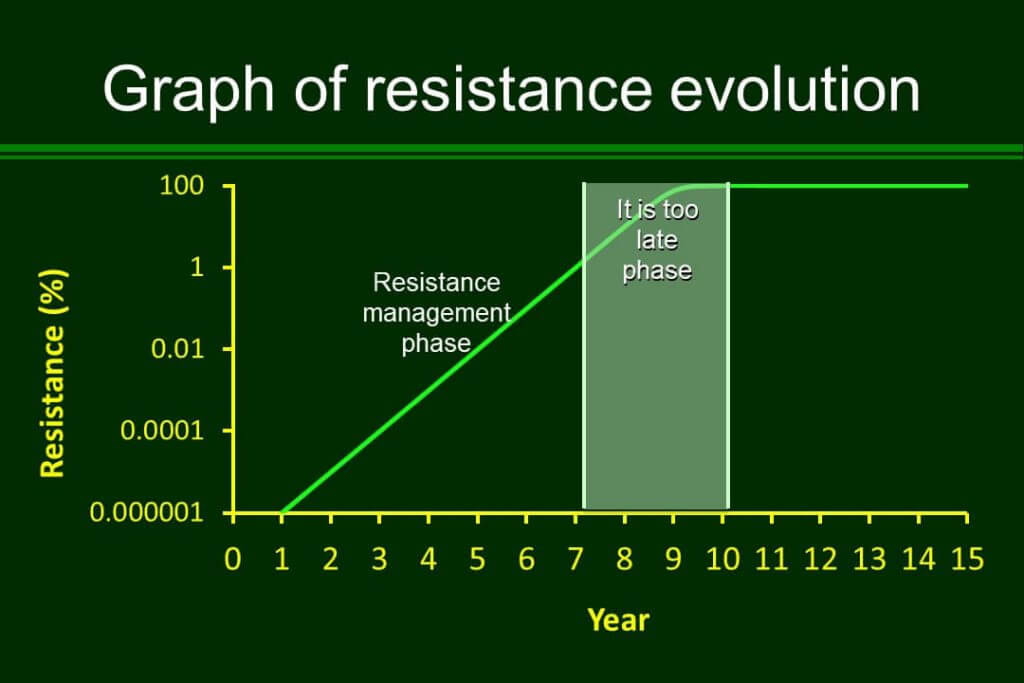

Assuming resistance is already in the field, even when not detected due to low levels (year 1 to 7 on the graph), farmers should manage resistance while still being in the “Resistance management” phase (graph#1). In this phase, herbicide resistance frequency is lower than 1% and often is not visible in the field.

At that stage, we can still manage the frequency of resistance and prevent these weeds from becoming problematic. Without resistance management tactics, the frequency of resistance can increase rapidly. This is when weeds will become very noticeable in the field and it will be difficult to manage the now resistant weed population (“Too late“ phase in Graph#1).

Graph#1: Resistance evolution

Herbicide management appears to be the most important factor contributing to weed resistance.

Questions such as “does management affect resistance or does resistance influence management?” are covered in this video to help farmers understand what they can do to prevent this problem.

Resources

- Bicksler AJ, Masiunas JB (2009) Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) suppression with buckwheat or sudangrass cover crops and mowing. Weed Technol 23:556–563

- Mirsky SB, Ackroyd VJ, Cordeau S, Curran WS, Hashemi M, Reberg-Horton SC, Ryan MR, Spargo JT (2017) Hairy vetch biomass across the eastern United States: effects of latitude, seeding rate and date, and termination timing. Agron J 109:1510–1519

- Mirsky SB, Curran WS, Mortenseny DM, Ryany MR, Shumway DL (2011) Timing of cover-crop management effects on weed suppression in no-till planted soybean using a roller-crimper. Weed Sci 59:380–389

- Myers R, Weber A, Tellatin S (2019) Cover crop economics: Opportunities to improve your bottom line in row crops. SARE Tech Bull

- PennState Extension (2010) Suppressing weeds usıng cover crops in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania State University

- Ruis SJ, Blanco-Canqui H, Creech CF, Koehler-Cole K, Elmore RW, Francis CA (2019) Cover crop biomass production in temperate agroecozones. Agron J 111:1535–1551

- Snapp SS, Swinton SM, Labarta R, Mutch D, Black JR, Leep R, Nyiraneza J, O’Neil K (2005) Evaluating cover crops for benefits, costs and performance within cropping system niches. Agron J 97:322–332

Authors

- Mark VanGessel

- Kara Pittman

- Victoria Ackroyd

- Michael Flessner

- Lovreet Shergill

- Claudio Rubione